She-Tragedy:

the spectacle of female suffering

Photograph of Vivien Leigh as Blanche DuBois in the film adaptation of A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951

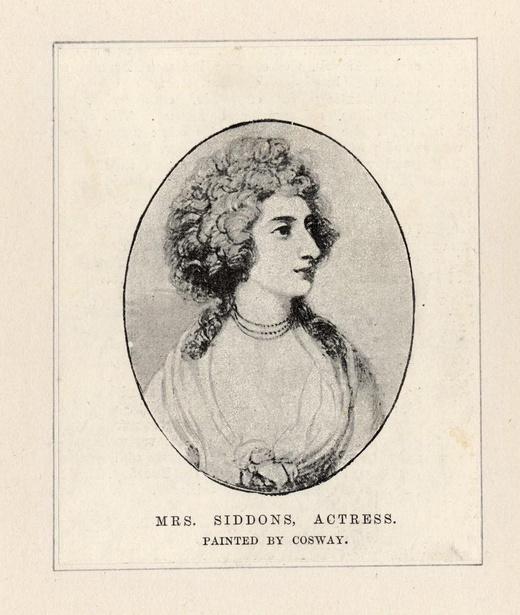

Mrs. Siddons by Thomas Gainsborough, 1727-1788

Introduction

an overview of she-tragedy

In the eighteenth century, she-tragedy, a genre dedicated to depicting the pathetic sufferings of women was immensely popular. After committing a sexual sin, usually an instance of lust or promiscuity, the woman is ‘punished’ with an off-stage rape or the loss of a child, husband, or lover. Afterward, the tragic woman descends into madness, commits suicide, or dies by natural causes. Despite the tragic and gruesome nature of this genre, these plays captivated audiences and consequently created extraordinary roles for tragic actresses. These actresses became memorialized through the writings of playgoers, artistic renderings of particularly touching scenes, and for some, their written reflections on their performances.

These documents provide insight into the blurring boundaries between actress and character, while also placing these tragic figures into a lineage that continues into the contemporary moment. This exhibition will explore this linage through writings, paintings, engravings, and photographs before making connections to present-day actresses whose emotionally charged moments have afforded them a similar celebrated celebrity status. Additionally, this exhibit will explore how notions of she-tragedy are still present in contemporary art through the continued engrossment of female suffering.

At the end of the seventeenth century, women began to take the stage for the first time. Although little is known about her life, it is supposed that the first female, English actress, Anne Marshall, took the stage in the tragic role of Desdemona during a 1660 production of Othello. This performance is memorialized through the prologue and epilogue written by Thomas Jordan, a poet who attended the 1660 performance and depicted the shocking, yet exciting sight of a woman on the stage. As women began to take on these tragic, leading roles, the internal, domestic, and private female experience became available for public consumption – a spectacle that propelled many women into stardom, celebrity, and consequential agency.

The most well-known actress during the restoration was Elizabeth Barry, who was known for her tragic roles. As Barry grew in popularity, roles were crafted and formed around her, and ultimately solidified by her engrossing performances. After creating the pathetic role of Monimia in Otway’s The Orphan, her success in the role and the declining popularity of heroic dramas allowed tragedies centered around pathetic, pure women to blossom. Despite her popularity, Barry was often speculated to be a prostitute, as no ‘respectable’ woman sought out becoming an actress. The theater exploited this negative view of actresses and female sexuality, as actresses often starred in suggestive scenes or moments of intense, sexual violence. The spectacle of female sexuality and the popularity of pathetic, female characters illustrate the beginnings of the genre of she-tragedy, which was ultimately popularized by Barry’s performances.

As the genre of she-tragedy grew throughout the eighteenth century, tragic actresses like Sarah Siddons rapidly gained popularity. Siddons was most famous for her portrayal of Lady Macbeth, and emerged from this stardom an empowered individual, who often bolstered the characters she played with researched, nuanced, and complex performances. Siddons portrayed Lady Macbeth with sympathy and sincerity, but also an immense power that fascinated audiences. Considered the Tragic Muse, Siddons was memorialized through playgoers’ artistic renderings, which most often depicted her as Lady Macbeth. These caricatures or commanding portraits illustrate a blurring boundary between actress and character that persists into the contemporary moment.

Although the genre of she-tragedy is most often associated with the eighteenth century, aspects of this genre continued into the nineteenth century with the popularity of melodramas, which allowed tragic actresses like Sarah Bernhardt to rise to fame. As actresses began to be viewed more positively, actresses like Bernhardt were able to capitalize on their popularity. Bernhardt traveled the world on multiple theatrical tours, in which she performed melodramas in sold-out theaters of her adoring fans. Because these tours were lucrative, Bernhardt was afforded an economic agency that set her apart from her predecessors. Her fame and fortune allowed her to take on business ventures, management positions within the theater, and performances in untraditional roles.

Throughout the twentieth century, starlets like Vivien Leigh gained fame through traditional theater as well as film productions, which rapidly increased their popularity and expansive celebrity. The rise of photography and the prevalence of billboards, flyers, posters, and magazines gave fans a more intimate picture of their favorite celebrity’s lives. Like the genre of she-tragedy as a whole, photography portrayed female subjects in emotional, intimate, and new ways that entranced audiences. Leigh was often depicted in behind-the-scenes photographs that showed her adjusting her hair and makeup, chatting with co-stars, or practicing her lines. Despite this in-depth look at Leigh’s private life, Leigh often suffered from manic depressive episodes, illness, and exhaustion from over-working. Her life often paralleled the tragic figures she portrayed, most notably, Blanche DuBois in the theatrical and Hollywood productions of A Streetcar Named Desire.

In the twenty-first century, the most popular films and theatrical productions often take the form of drama, comedy, or the hybrid genre of the dramedy. Much like the melodrama, I see the dramedy as a modernized sub-genre of tragedy, with many contemporary dramedies including notable elements of she-tragedy. Despite major social, cultural, and even political progress for women in the modern era, female sexuality and suffering still remain a spectacle that encapsulates popular media. In her one-woman play and the subsequent television adaptation, Fleabag, British actress Phoebe Waller-Bridge includes several traditional notions of she-tragedy such as female sexual transgressions, consequential loss, and suicidal ideation. Both the theatrical and television productions of Fleabag were met with critical acclaim, speaking to the popularity of the hybrid genre of dramedy, as well as the continued engrossment with female sexuality and suffering that have immortalized the role of the tragic actress and allowed elements of she-tragedy to persist into the contemporary moment.

seventeenth century

Prior to the end of the seventeenth century, young men and boys were traditionally cast in female roles on the professional stage in England. Actors like Edward Kynaston were famous for their beautiful, emotional, and convincing portrayals of female characters. However, a shift occurred when the theaters reopened in 1660. On December 8, 1660, during a King’s Company production of Othello, a woman took the English stage in the role of Desdemona. Although this woman remains unidentified, she is supposed to be Anne Marshall. After Marshall’s debut, it quickly became customary for women to act in female roles and actresses like Elizabeth Barry gained popularity, despite the negative connotations surrounding those who sought careers as actresses.

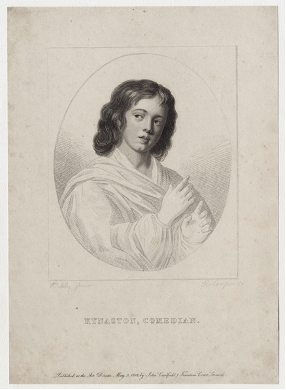

Stripple engraving of Edward Kynaston by Robert Cooper, 1818.

Before the late seventeenth century, young men like Kynaston were cast in female roles on the professional stage in England. Kynaston is depicted with young, feminine features making him a popular and convincing choice for female roles.

Print of Elizabeth Barry by Godfrey Kneller, 1792.

A Prologue to introduce the first Woman that came to

Act on the Stage in the Tragedy, call'd The Moor of Venice

.

I Come, unknown to any of the rest

To tell you news; I saw the Lady drest;

The Woman playes to day; mistake me not,

No Man in Gown, or Page in Petty-Coat;

A Woman to my knowledge, yet I cann't

(If I should dye) make Affidavit on't.

Do you not twitter Gentlemen? I know

You will be censuring; do't fairly though;

'Tis possible a vertuous woman may

Abhor all sorts of looseness, and yet play;

A Prologue to introduce the first Woman that came to

Act on the Stage in the Tragedy, call'd The Moor of Venice by Thomas Jordan, 1660.

On December 8, 1660, poet Thomas Jordan wrote in response to watching a woman play the part of Desdemona in a production of Othello by the Kings Company at the Vere Street Theater. Jordan claims he not only saw her on the stage, but saw her before the show in private, further confirming the actress was indeed a woman. This actress remains unidentified but is most likely Anne Marshall.

Barry popularized tragedies, especially those centered around pathetic, pure women. Her influence spurred the beginnings of she-tragedies and their later popularity in the 18th century.

Epilogue.

ANd how d'ye like her▪ come, what is't ye drive at▪

She's the same thing in publick as in private;

As far from being what you call a Whore,

As Desdemona injur'd by the Moor▪

Then he that censures her in such a case

Hath a soul blacker then Othello's face:

But Ladies what think you? for if you tax

Her freedom with dishonour to your Sex,

She means to act no more, and this shall be

No other Play but her own Tragedy;

She will submit to none but your commands,

And take Commission onely from your hands.

Jordan explicitly links Marshall to the character she portrays – the tragic Desdemona. Although Anne Marshall’s female portrayal of highly emotional, intimate scenes made her a sensation, she was quickly forgotten. Tragically, despite the notoriety ascribed to the first female actress, Anne Marshall’s story remains widely unknown to this day.

eighteenth century

As theater continued to blossom as a popular pastime in the eighteenth century, actresses achieved new levels of celebrity, and consequential agency. Female actresses, especially those in tragic roles, became expected and celebrated additions to the English stage. After joining the Drury Lane company in 1775, tragic actress, Sarah Siddons, rapidly gained popularity and was widely known for her sincere and sympathetic portrayal of Lady Macbeth in Macbeth. She performed the role from the 1770’s until her retirement from the stage in 1812. Siddons’ dedication to the role allowed her to bring new complexities to the character through her acting and eventual publications on the subject. While Lady Macbeth greatly seemed to inspire Sarah Siddons, Siddons as Lady Macbeth became a muse in her own right.

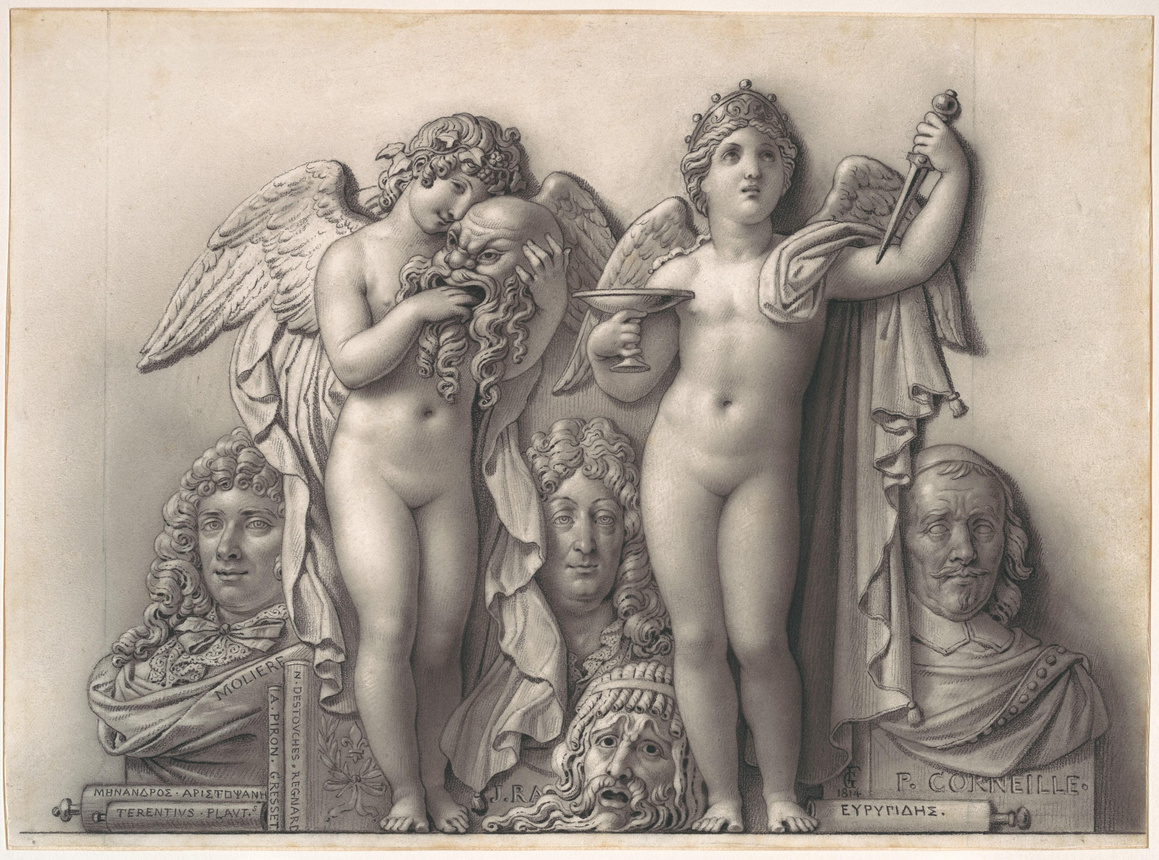

Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse by Sir Joshua Reynolds, oil on canvas, 1783-84

Because of the complexity, emotion, and sympathy Sarah Siddons brought to her portrayal of tragic, female characters, Siddons became a muse in her own right, prompting numerous artistic renderings of her. Siddons is depicted as an imposing, decadent figure, illustrating her grandeur and celebrity.

Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggers, by Henry Fuseli, oil paint on canvas, exhibited 1812

This painting is also known as Mrs. Siddons as Lady Macbeth, as it is thought to be inspired by Sarah Siddons’ portrayal of Lady Macbeth, although it is not a direct portrait. In this scene, a horrified Macbeth emerges with bloodied daggers and is met with his wife, who seizes control of the situation. Fuseli depicts Lady Macbeth as spectral and imposing, almost looming over the shrunken Macbeth.

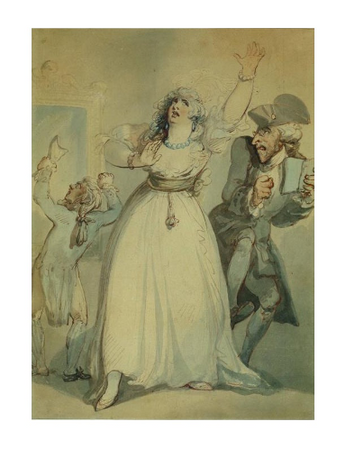

Mrs. Siddons Rehearsing by Thomas Rowlandson, pen and watercolor drawing

This simple drawing is a caricature, meant to satirically depict Siddons’ emotional and eclipsing performativity. Despite this negative illustration, theatergoers continued to be drawn to her performances of tragic figures.

Mrs. Siddons has left, in her Memoranda, the following

“Remarks on the Character of Lady Macbeth.”

In this astonishing creature one sees a woman in whose bosom the passion of ambition has almost obliterated all the characteristics of human nature; in whose composition are associated all the subjugating powers of intellect and all the charms and graces of personal beauty. You will probably not agree with me as to the character of that beauty; yet, perhaps, this difference of opinion will be entirely attributable to the difficulty of your imagination disengaging itself from that idea of the person of her representative which you have been so long accustomed to contemplate. According to my notion, it is of that character which I believe is generally allowed to be most captivating to the other sex, — fair, feminine, nay, perhaps, even fragile —"

Published within poet Thomas Campbell’s 1834 biography of Sarah Siddons, Siddons’ notes on her famous character offer an intimate and in-depth look at her deep understanding of Lady Macbeth. Even in her short descriptions of the character, one can see the great sympathy and complexity that Siddons sees within the tragic character.

nineteenth century

In the nineteenth century, genres such as melodrama dominated the theater, offering scenic and emotional performances, alongside traditional, ever-popular Shakespearian tragedies. Sarah Bernhardt, a French actress born in Paris in 1844, rose to fame throughout this period by performing famed melodramas. Eventually, Bernhardt’s popularity allowed her to travel the world on lucrative, sold-out theatrical tours. With economic success and immense celebrity, Bernhardt achieved new levels of agency that allowed her take on management positions within the theater and perform in untraditional roles.

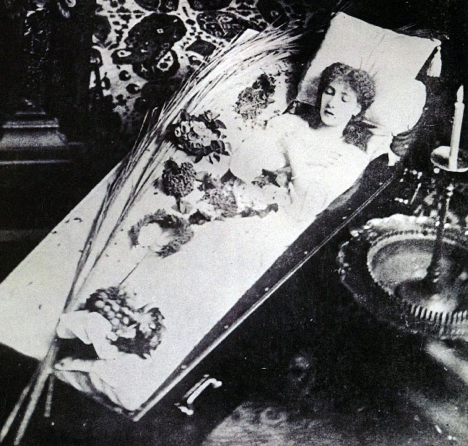

Sarah Bernhardt photographed sleeping in a coffin

Known for her quirky, melodramatic off-stage persona, Bernhardt reported traveling with a coffin, in which she often slept.

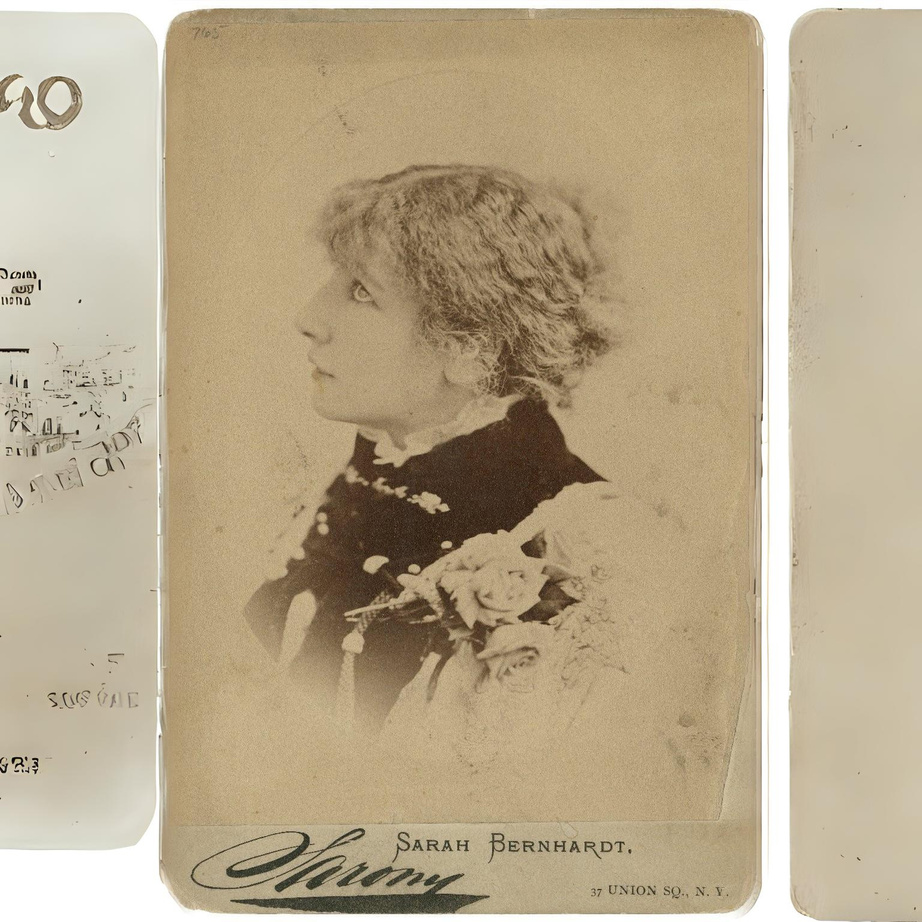

Sarah Bernhardt photographed by Napoleon Sarony, 1880

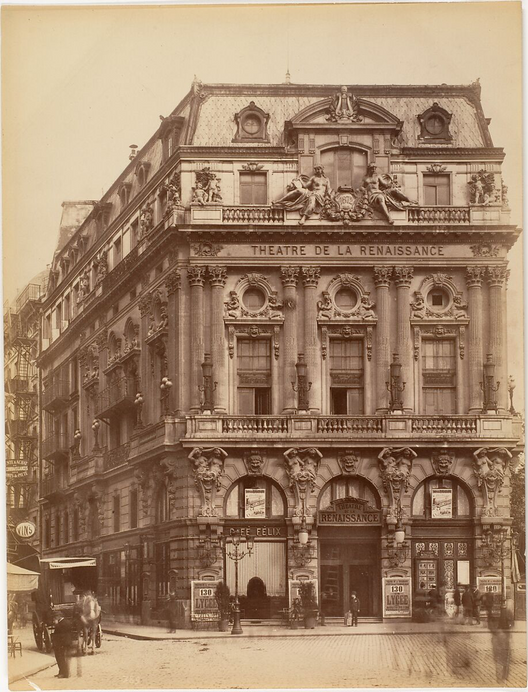

Photograph of Théâtre de la Renaissance, unknown, 1890

In 1893, Sarah Bernhardt purchased the Théâtre de la Renaissance for 700,00 francs. From 1893 to 1899, she served as the lead actress and artistic director, in which she managed all aspects of the theater including marketing, lighting, costuming, and performing. She produced several successful plays but was forced to give up the theater in 1898 due to financial hardship.

In this photograph, she is depicted with decadent styling of the time, illustrating her wealth, status, and celebrity.

Fantastic Inkwell (Self-Portrait as a Sphinx), sculpture by Sarah Bernhardt, 1880

Bernhardt was also a talented sculptor and created this self-portrait depicting her as a sphinx. The masks of tragedy and comedy appear on her shoulders in reference to her acting career

Photograph of Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt, unknown

In 1898, Bernhardt leased the Parisean theater, Théâtre des Nations, and renamed it the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt. She completely renovated the space and put on a series of successful plays including Hamlet, where she played the titular role. The theater kept its name until occupation of France during World War II.

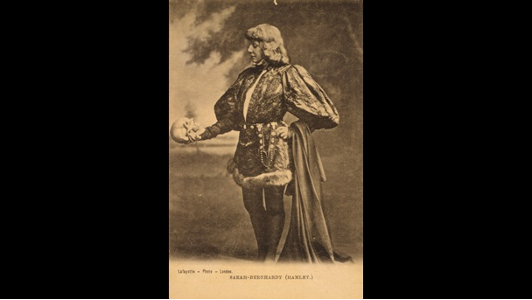

In 1877, Bernhardt was gifted a human skull by novelist Victor Hugo. She later used the skull in her production and performance of Hamlet.

Photograph of Sarah Bernhardt as Hamlet, 1899

This photograph depicts Sarah Benhardt in her titular role in Hamlet. Bernhardt played the masculine character with a strong, yet feminine energy and it became one of her most notable, albeit unconventional, roles.

twentieth century

In the twentieth century, there were many shifts in theater that broadened the scope of acceptable acting methods, enjoyable genres, and the celebrity of female actresses. Although theatrical productions were still celebrated, many notable actresses of this time, such as Vivien Leigh, garnered status from film productions. In addition to her popular theater and film productions, Leigh was photographed for advertisements, posters, and behind the scenes footage. These media became rapidly accessible to the public, which only enhanced the spectacle of her talent and beauty. However, behind her immense beauty and radiant personality, Leigh often suffered from manic depression and exhaustion from over-performing. The characters she played, most-notably, Blanche DuBois in both the play and film of A Streetcar Named Desire, mimicked the behind-the-scenes tragedies Leigh experienced during her life.

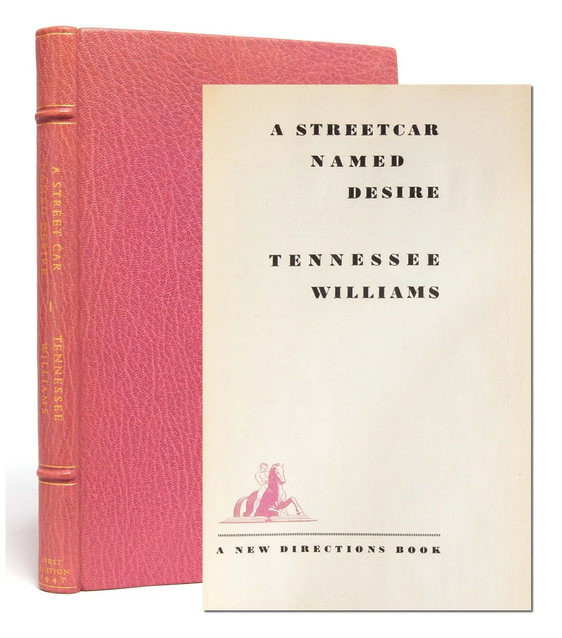

A Streetcar Named Desire, First Edition, by Tennessee Williams, 1947

Despite being a twentieth century American play, A Streetcar Named Desire follows many conventions of she-tragedy. Blanche commits many sexual transgressions throughout the play, is consequently ostracized from those around her, assaulted, and forced into a psychiatic institution.

Photograph of Vivien Leigh and Marlon Brando on set for A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951

Leigh was well liked on set and became close friends with her co-stars. She maintained friendships with Marlon Brando as well as Tennessee Williams and his partner, Frank Merlo. Williams admired her talent but argued that Leigh’s personality and friendship are what he cherished most. Similarly, Marlon remarked on Leigh’s immense beauty and similarities to Blanche DuBois in his autobiography.

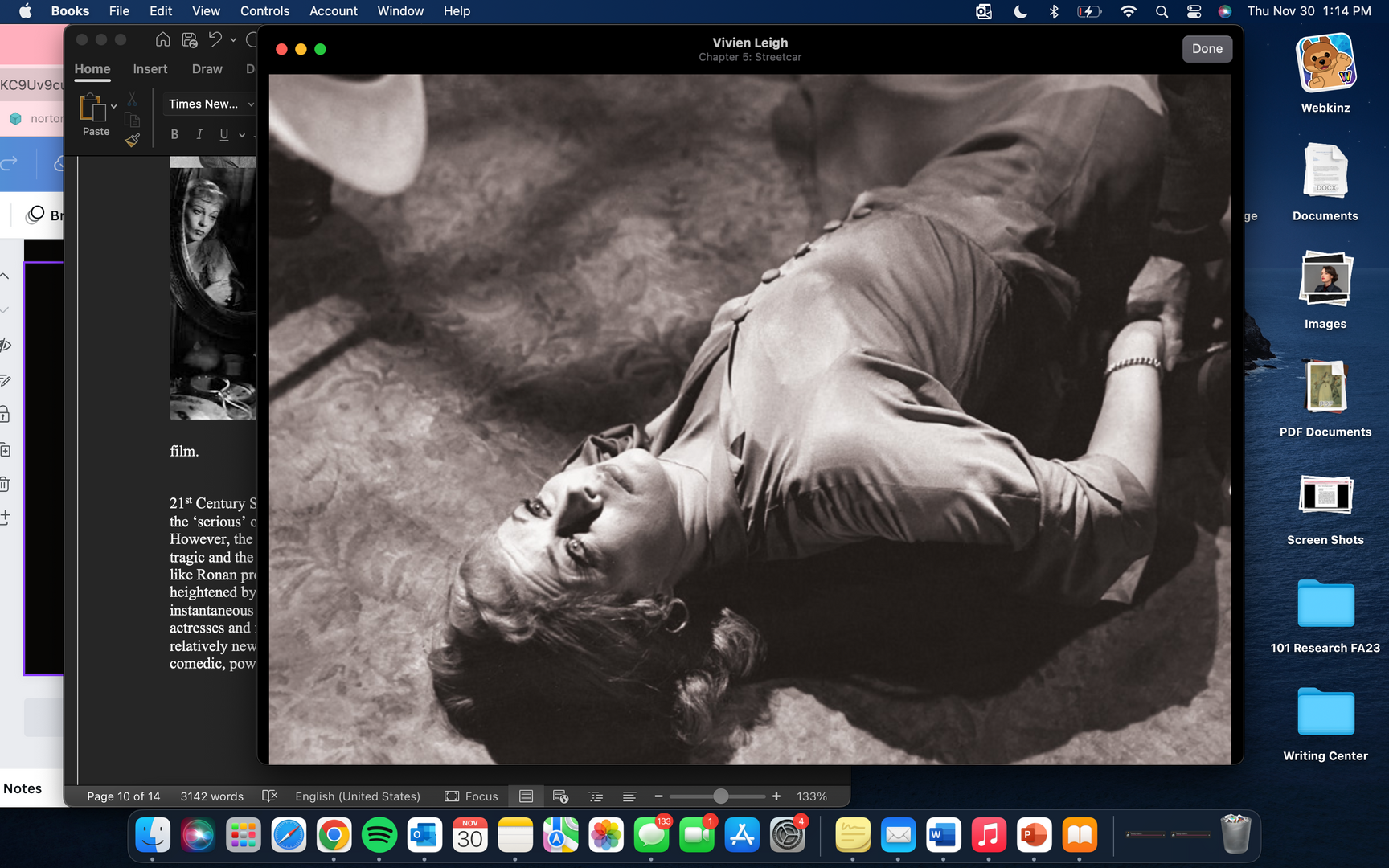

Photograph of Vivien Leigh as Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951

Although Leigh was excited to collaborate with director, Elia Kazan, the two disagreed over Vivien’s depiction of Blanche. Kazan was “irritated” by Blanche, while Leigh was moved by the character and portrayed her with sympathy. However, after seeing Leigh’s performance, the two finally came to an agreement.

Still of Vivien Leigh as Blanche Dubois in the final scene of A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951

“Everyone said I was mad to try it. They are often saying I am mad to try things, but Blanche is such a real part, the truth about a woman with everything stripped away. She is a tragic figure and I understand her.” – Leigh on her role as Blanche

twenty- first century

In the twenty-first century, tragedy has become harder to define. Sub-genres like she-tragedy and domestic tragedies have broadened the scope of what is considered traditionally tragic. Similarly, drama, comedy, and the hybrid genre of dramedy have become popular within film and theater alike. Although the genre of she-tragedy has faded, conventions of the genre live on in modern day productions, even those that mix the dramatic and comedic. One such production is the 2016 limited series, Fleabag, starring British actress, Phoebe Waller-Bridge. The television series is based off of Waller-Bridge’s 2013 one-woman play that premiered at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Despite being categorized as a dramedy or black comedy, both the play and television adaptation of Fleabag contain modernized elements of she-tragedy, as the main character, the unnamed, Fleabag, continuously commits sexual offenses, experiences ‘punishment’ in the loss of her best friend, and ultimately contemplates suicide.

Promotional poster for the one-woman play, Fleabag, written and performed by Phoebe Waller-Bridge, 2019

In 2013, the play premiered at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the world’s largest performance arts festival, where it received the Fringe First Award. In 2021, Waller-Bridge was announced as the honorary President of Edinburgh Festival Fringe Society, where she launched the ‘Keep it Fringe’ fund, a £100,000 fund for Fringe artists.

Promotional posters for the 2016 television adaptation of Fleabag, written by and starring Phoebe Waller-Bridge.

The TV adaptation of Fleabag was met with immense critical acclaim. Waller-Bridge won the British Academy Television Award for Best Female Comedy Performance for the first season of the adaptation. The second season was nominated for 11 Primetime Emmy Awards, and won awards for Outstanding Comedy Series, Outstanding Lead Actress, and Outstanding Writing for a Comedy Series. Phoebe Waller-Bridge received a Golden Globe Award for Best Television Series and Best Actress.

Phoebe Waller-Bridge as Fleabag in the television adaptation of Fleabag.

Although she-tragedy is not a notable genre in the twenty-first century, modernized elements of the genre still exist in contemporary theatrical and film productions. Throughout Fleabag, the unnamed protagonist, Fleabag, is criticized for her sexual transgressions, such as sleeping with her best friend, Boo’s boyfriend. After discovering the affair, a distraught Boo accidentally commits suicide. At the end of the series, Fleabag herself contemplates suicide.

Phoebe Waller-Bridge as Fleabag in the television adaptation of Fleabag.

Both the theatrical and television productions of Fleabag were met with critical acclaim, speaking to the popularity of the hybrid genre of dramedies, as well as the continued engrossment with female sexuality and suffering that have immortalized the role of the tragic actress and allowed elements of she-tragedy to persist into the contemporary moment.